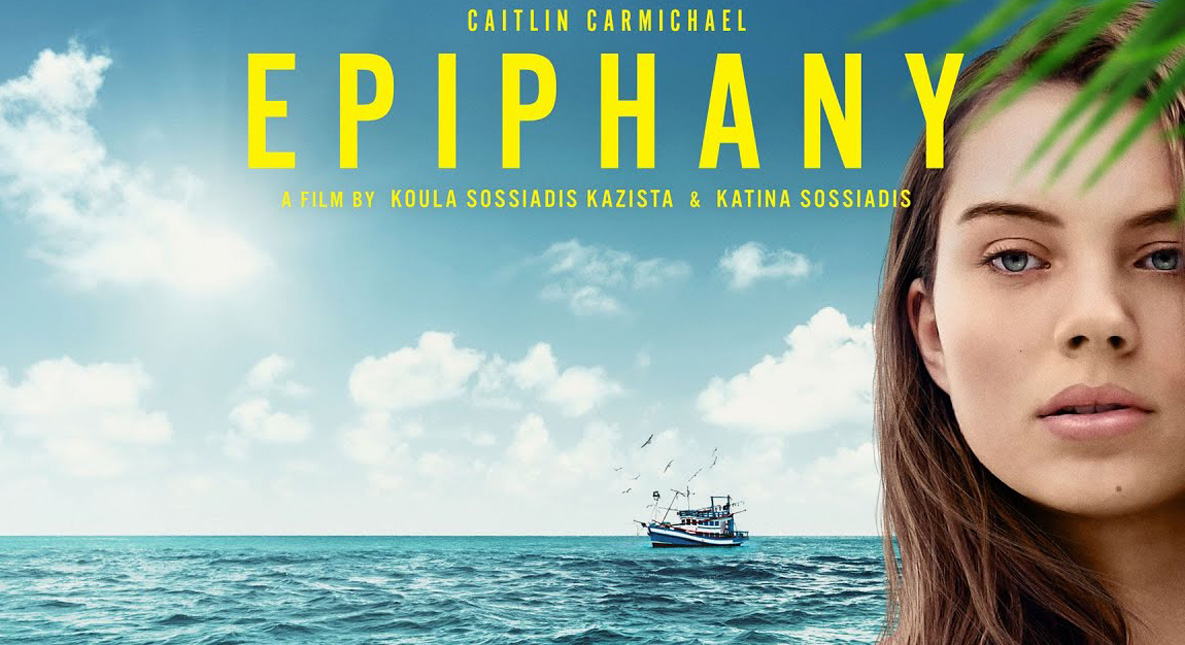

Alumna Explores Identity, Greek Culture in "Epiphany"

It isn’t every day that a movie’s protagonist is a teenage girl and first-generation U.S. citizen. In Epiphany, filmmaker and director Koula Sossiadis Kazista ’91 and her sister Katina Sossiadis craft the story of Luka, a girl who struggles to connect with herself, her family, and her Greek culture.

Like many of us, Luka struggles to juggle the feelings of isolation and identity. Throughout the film, soft music accompanies the vivid, scenic shots of Tarpon Springs, FL, a largely Greek-dominated town, which relies on sponge-diving for its main commercial revenue.

Despite so many people who share bits and pieces of her identity, Luka feels alone in the world and like an outsider in her own family. The film doesn’t just center on Luka’s search for her identity; it also dives deep into her cultural heritage, a reflection of Kazista’s own story. Kazista’s father was a Greek immigrant who came to the Lehigh Valley when he was 24 years old, where he began working as a garage-mechanic. She remembers witnessing the film’s title event as a child during the summers that her family spent in Tarpon Springs. The title of the film itself is a play on what Kazista describes as a “cinematic moment” in her own story, brought to life onscreen. The Epiphany is a Greek Orthodox tradition in which teenagers compete in diving for a cross – a symbol of hope thought to bring luck to the winner’s family. Yet, only boys are allowed to participate in this tradition.

When asked about the process of forming Luka’s identity, Kazista openly states that she originally had trouble writing the script from a teenage boy’s point of view. But once her sister joined her, they decided to scrap Lucas’ story and instead write Luka’s story – a teenage girl’s perspective.

By doing so, Kazista opens the door up to issues revolving around gender and being female in the Greek Orthodox Church. With Epiphany, to receive the cross means to receive luck and fortune. It means a way to solve problems, no matter how big or small they are. To Luka, this tradition is her only hope to fix her broken family. On the day of the Epiphany, Luka pulls a “Mulan,” disguises herself as a boy, and dives for the cross.

In the film, the characters are human – meaning, they are far from perfect. While directing the film, Kazista wanted to ensure that it did not fall face-first into the standard “happily-ever-after” trope. Each one of Epiphany’s characters carry with them a weight that crafts the raw humanity of Kazista’s story.

We have all been Luka at some point in our lives. Either that, or we have all known a “Luka.” Epiphany humanizes and validates our own feelings about our identities. The audience is brought along Luka’s journey of self-acceptance and liberation. Epiphany is Kazista’s ode to her Greek identity, and an ode to young girls all around the world. It’s a call to grow and to accept our pain that is ingrained in our identity.

Read this article and other content in the Spring 2020 Moravian Academy Journal.

myMA

myMA